Letter from Africa: How racism haunts black people in Italy

- Published

In our series of letters from African journalists, Ismail Einashe writes that many black people in Italy feel that racism is not taken seriously.

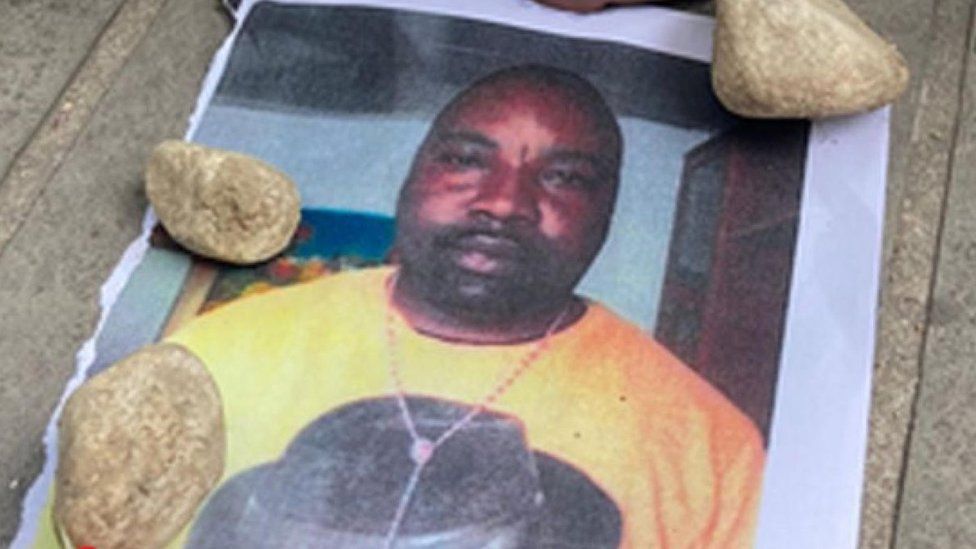

For Italian-Eritrean filmmaker and podcaster Ariam Tekle, there is no doubt that the recent killing of a disabled Nigerian street vendor, Alika Ogorchukwu, in Italy was a "racist murder".

This is despite the fact that local police have ruled out racism as a motive for the 39-year-old's killing in the seaside town of Civitanova Marche.

He was reportedly selling handkerchiefs when he was chased and beaten to death. None of those who witnessed the broad daylight attack appeared to intervene.

A suspect - a white man named as Filippo Claudio Giuseppe Ferlazzo - has been ordered to remain in jail as the investigation continues.

A police investigator said Mr Ogorchukwu was attacked after the trader's "insistent" requests to the suspect and his partner for spare change.

Nevertheless, his horrific murder - caught on video - has firmly put the spotlight on racism in Italy.

In 2016 another Nigerian man, Emmanuel Chidi Namdi, was killed after defending his wife from racist abuse in the town of Fermo in central Italy.

Two years later, a far-right extremist shot six African migrants in a drive-by attack in a town about 25km (15.5 miles) from where Mr Ogorchukwu was killed.

When the police arrested him, he was wrapped in the Italian flag shouting "Viva l'Italia", telling police he wanted to "kill them all".

In fact this region of Le Marche has been governed since 2020 by the far-right party Fratelli d'Italia (Brothers of Italy).

It is led by Giorgia Meloni, who could become Italy's first female prime minister if she wins a snap election to be held in September.

The party, which is expected to emerge as the single largest, is part of a wider conservative bloc that includes the right-wing Lega (League), led by Matteo Salvini and the conservative Forza Italia (Forward Italy), led by former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi.

Ms Tekle says black people in Italy regularly experience racist violence, police harassment and discrimination, and the rise of far-right anti-immigration parties has "normalised" racism.

But, she adds, most Italians grow up with the attitude that racism is not that serious in their country.

"They always say it's 'ignorance' or something else. They don't want to admit that there is racism in Italy. They always say America or the UK is worse."

In recent years Italy, a country long known for its history of mass emigration, has become one of Europe's migrant hotspots.

The country has struggled to cope with this historic reversal and to integrate migrants successfully into Italian society.

Ms Tekle was born and raised in a working class neighbourhood in the city of Milan. Her family has been in Italy for five-decades, yet she feels marginal in a society that, she says, refuses to see her as one of them.

"I speak with a Milanese accent but they ask me all the time where I am from."

Italy also makes it more complicated for those born to migrant parents to obtain Italian citizenship - it is not an automatic right and they have to wait until they are 18 to apply, making them feel more like outsiders.

Alessia Reyna, a student and member of an anti-racist network, says that even though she is very Italian, she will never be recognised as such because she is a black woman.

Ms Reyna was born in Rome to an African-American father and Afro-Peruvian mother, who met outside the Colosseum of the eternal city and fell in love.

She grew up in a small town near Milan. She went to school there, but chose to continue her studies in the UK.

Ms Reyna says that Italy is not ready to look at issues of structural racism.

She points to another recent case when Beauty Davis, a young Nigerian who worked as a dishwasher in a restaurant in Calabria in the south of Italy, was allegedly slapped after she demanded her wages.

"She just asked to be paid, but she was attacked. I don't think a white woman would have been attacked," Ms Reyna says.

Ubah Cristina Ali Farah, the award-winning Italian-Somali novelist, expresses a similar view.

She says that very few Italians are aware about the colonial history of their country and how this might impact on the experiences of non-white Italians.

Italy was the colonial power in Eritrea, Somalia, Libya and also occupied Ethiopia in the 1930s under Benito Mussolini's fascist regime.

Ms Ali Farah's family has been in Italy for more than half a century, but she says: "If they don't recognise those of us with colonial ties to Italy as being Italian, how will they ever recognise those people who arrived on boats to Italy or their children as Italian".

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica