Las Vegas murder case cracked with smallest ever amount of DNA

- Published

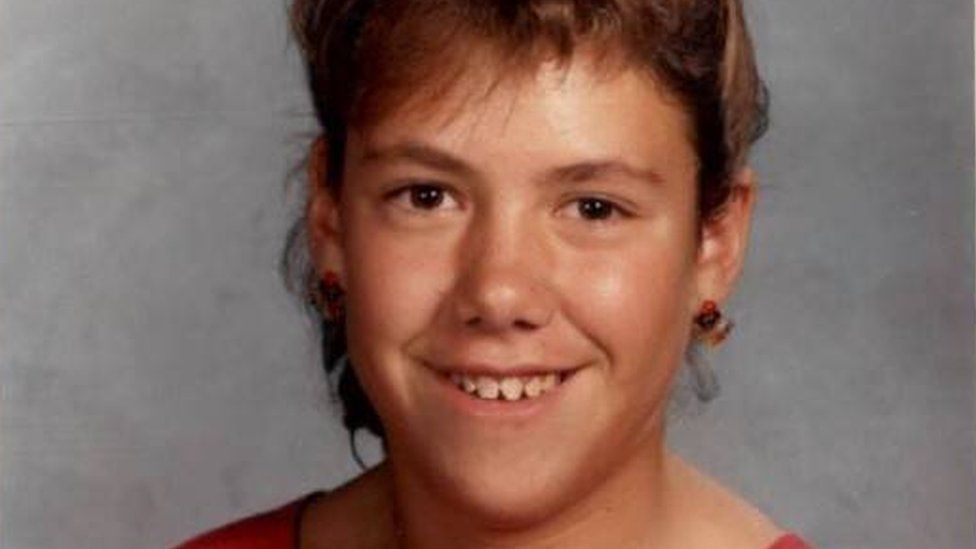

The 1989 murder of a 14-year-old girl in Las Vegas has been solved by using what experts say is the smallest-ever amount of human DNA to crack a case.

Stephanie Isaacson's murder case had gone cold until new technology made it possible to test what little remained of the suspect's DNA: the equivalent of just 15 human cells.

Police on Wednesday said they had identified the suspect by using genome sequencing and public genealogy data.

Her alleged killer died in 1995.

"I'm glad they found who murdered my daughter," Stephanie's mother wrote in a statement that was read to reporters at Wednesday's news conference.

"I never believed the case would be solved."

Thirty-two years ago, Stephanie's body was found near the route she normally walked to school in Las Vegas, Nevada. She had been assaulted and strangled.

This year, police were able to pick up the case again after a donation from a local resident. They turned over the DNA samples left to Othram, a Texas-based genome-sequencing lab that specialises in cold cases.

Typical consumer DNA testing kits collect about 750 to 1,000 nanograms of DNA in a sample. These samples are uploaded to public websites specialising in ancestry or health.

But crime scenes may only contain tens to hundreds of nanograms of DNA. And in this case, only 0.12 nanograms - or about 15 cells' worth - were available for testing.

Using ancestry databases the researchers were able to identify the suspect's cousin. Eventually they matched the DNA to Darren Roy Marchand.

Marchand's DNA from a previous 1986 murder case was still on record, and was used to confirm the match.

He was never convicted and died by suicide in 1995.

The genomic technology used to solve the case is the same that was used to catch the notorious Golden State Killer in 2018.

"This was a huge milestone," Othram chief executive David Mittelman told the BBC.

"When you can access information from such a small amount of DNA, it really opens up the opportunity to so many other cases that have been historically considered cold and unsolvable."

The company is currently working on cases dating back as far as 1881.

Related Topics

- Published29 April 2018

- Published16 July 2021