Coronavirus: Why has Melbourne's outbreak worsened?

- Published

For months Australia has felt optimistic about containing Covid-19, but a resurgence of the virus in Melbourne has put those efforts at a critical stage.

About 300,000 people were ordered back into lockdown this week amid a military-assisted operation to "ring fence" 10 postcodes at the centre of the outbreak.

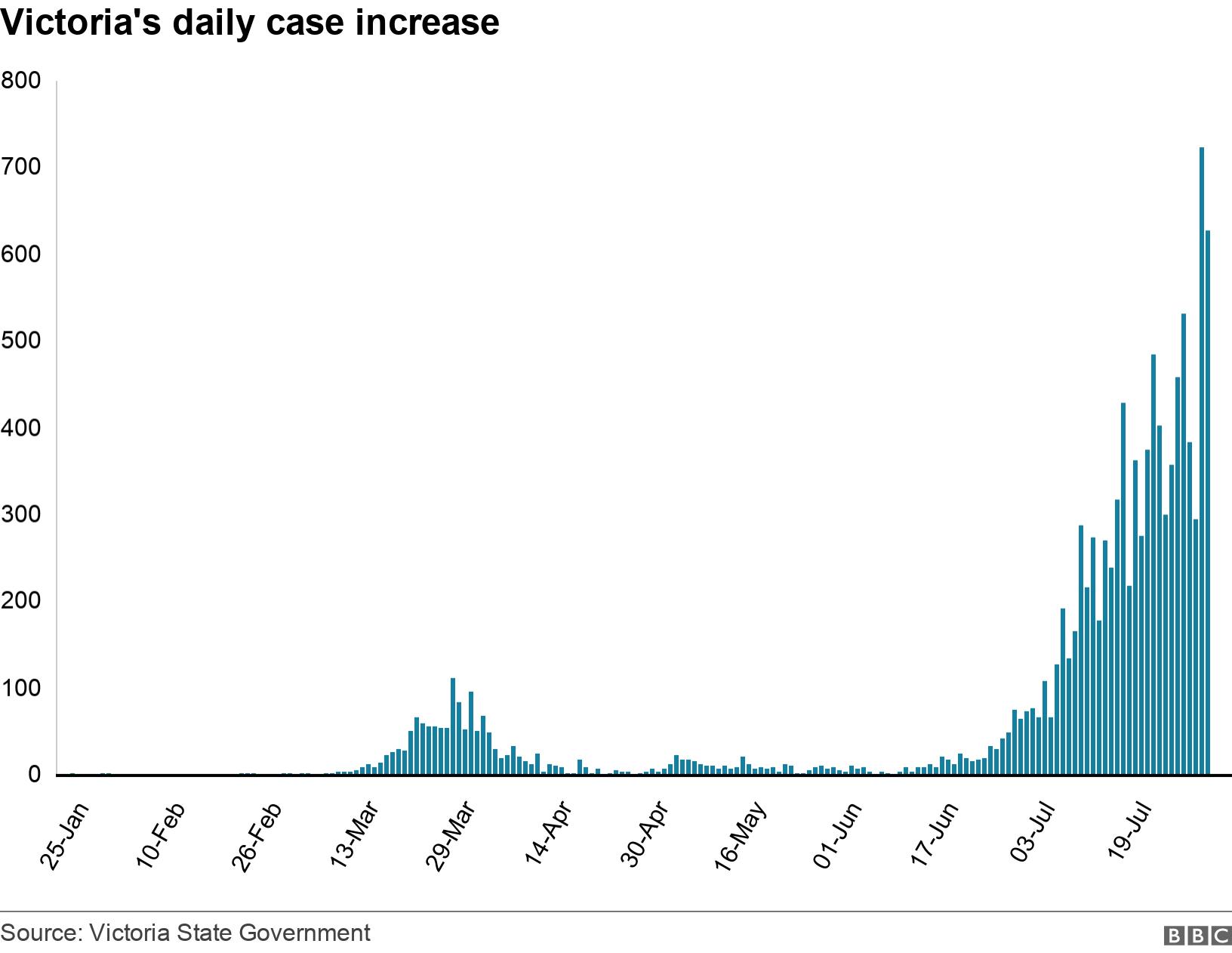

The problem has escalated in the past fortnight - there are now 482 active cases in the state of Victoria.

The numbers remain below Australia's March peak, but what's concerning to authorities is that local transmission is now the key source of infections.

Previously, most cases were coming from travellers returning from overseas. Australia's curve flattened rapidly three months ago with the enforcement of lockdowns and mandatory hotel quarantines for people entering the country. It has had about 8,000 cases in total and 104 deaths.

In every other state, the virus has been dramatically slowed or eradicated. So what's gone wrong in Victoria?

There have been failures in hotel quarantine

Premier Daniel Andrews has pinpointed the origin of many infections to workers overseeing hotel quarantines breaking the rules. More than 20,000 travellers have gone through 14-day quarantine in the state.

A report which traced Covid-19's mutation in Victoria found that hotel staff cases were the "ancestors" of ones found later in suburban homes.

So how did the virus spread? Allegations of blame have been levelled at private security firms contracted to operate the state's quarantine. Neighbouring New South Wales took a different approach - using the police force.

Victoria has faced accusations of systemic failures such as guards being improperly trained or not given enough PPE.

Mr Andrews has also described cases of illegal socialising between staff, listing examples of workers sharing a cigarette lighter or car-pooling. Local media also reported claims of sex between guards and quarantined travellers.

The government has ordered a judicial inquiry into their quarantine operation and fired the contractors.

Unlike in many states, the virus had been 'seeded'

In early May - during Australia's lockdown - authorities expressed concern about a virus cluster among workers at an abattoir in Melbourne's west.

About 111 cases were eventually linked to the site, which had been the subject of a rapid trace-and-track response from authorities.

Lockdown restrictions eased a month later, allowing people to again visit friends and family, and enjoy other freedoms such as eating out at restaurants.

But experts believe that secondary cases from that cluster - and possibly others - were still festering undetected in the community.

"It seeded the population… and there were enough cases out there when the precautions relaxed," Prof John Matthews from the University of Melbourne tells the BBC.

Some became complacent as freedoms returned

With the relaxation of lockdown and Australia's apparent success, the public also became less vigilant, experts say.

Officials were still exhorting social distancing, but group limits were expanded. Large family groups reconnected and some cases stemmed from people with mild symptoms attending those gatherings, authorities said.

"Once the feeling got around that it was over - when it really wasn't - Victoria copped it," says Prof Matthews.

Allegations of poor messaging to non-English-speaking communities

The locked-down "hotspots" in Melbourne's north and west are also home to large migrant communities.

Leaders from those areas have argued that communication of public health orders was insufficient for non-English speakers, and this was exacerbated as restrictions rapidly changed throughout May.

Given Melbourne's significantly multicultural make-up - a language other than English is spoken in almost 35% of households - this was a notable oversight, critics said.

Researchers have also found that translations were inadequate, materials weren't being circulated, and there were even allegations of government agencies falsifying communications.

It's also just 'bad luck', experts say

Authorities have always emphasised that such outbreaks would be inevitable once Australia's lockdown lifted. In recent weeks, they've said the situation in Victoria could have happened anywhere.

So why Melbourne and not Sydney, for instance - Australia's other comparably sized city? Sydney has Australia's busiest airport and exited lockdown two weeks before Melbourne. It also, broadly, had looser lockdown measures.

Health officials have said that much of it is probably a matter of "bad luck".

The genomic report has added some more information - that similar violations in hotel quarantine have not been reported in Sydney. The report has not been released publicly but has been referenced by state officials.

But much of the whole-picture evidence remains circumstantial, says Prof Mathews, who adds that Victorians have been unfortunate to experience both the meatworks and quarantine issues.

So what now?

Other states have banned travel to and from the Melbourne "hotspots", and implemented other measures.

Prof Matthews says authorities are "throwing everything at it" to halt the spread "but nevertheless, we're at quite a critical stage".

"If you can't stop the spread - you lose control - you get to the stage where you can't keep up with contract tracing… essentially what happened in Europe and North America."

For now, Australia remains in a far better position than most nations. Only 23 people with the virus are in hospital in Victoria, and testing is widespread and rigorous - over 2.5 million tests have been conducted in a national population of 25 million.

"It's hard to say where we'll be in a month's time", says Prof Mathews. "We used to say Australia's response was one of the best in the world. And we can still say that, but with the qualification that we got caught."

Reporting by the BBC's Frances Mao

- Published25 June 2020

- Published22 June 2020